by Puey Ungphakorn

To cite this article: Puey Ungphakorn (1977) Violence and the military coup in Thailand, Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars, 9:3, 4-12,

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14672715.1977.10406422

Note: Puey Ungphakorn was in 1975 appointed Rector of Thammasat University. On the evening of the bloody 6 October 1976 Massacre, Puey resigned from his position as rector of Thammasat in protest against the bloodbath that had occurred that day on the university campus. Realising he was a marked man, Puey went to Don Mueang airport where he was met by a lynch mob. Only with the help of the Royal Thai Air Force Air Police, who had been instructed by King Bhumibol’s privy council office to help him leave, did he evade death and get on a plane bound for London.

On the evening of October 6, 1976, a so-called “National Administrative Reform Council” declared a military take-over in Thailand. On the following days the menacing, jowled faces of the military junta appeared, counterparts of their like in

Chile, Greece, and elsewhere. A bland B.B.C. announcement spoke of the return to normality in Bangkok, and the indifference, or even satisfaction, of the majority of the population. It seemed that the horror of a few hours’ barbarity in Bangkok’s Thammasat University had happened in a blink of the world’s eye, of little interest in an international media accustomed to tragedy, and of little

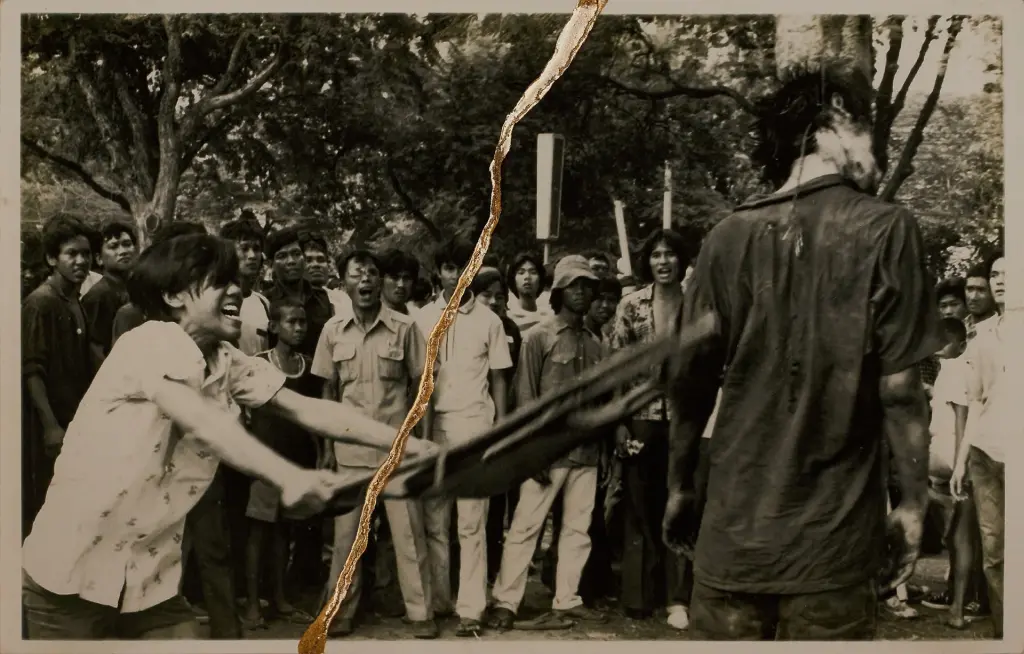

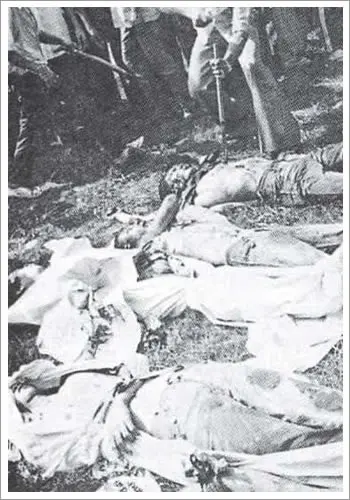

importance in the process of affairs. But one cannot study the photographs of those terrible hours on October 6th without questioning the hatred that broke out. Just three years before, identical almost to the day and place, the military had gunned down seventy-one students and others: the price of the overthrow of the dictatorship of Thanom Kittikichorn and his deputy Prapas Charusathiara. In those days the students were acclaimed heroes of the people.

In 1976, the actors changed their clothes. Prapas and Thanom reentering respectively as a self-professed invalid and a Buddhist monk, while, as the government media repeated endlessly, the “people” turned on the students with inhuman savagery. What had happened in the interval?

Up to the present the military coup has taken the accustomed course: massive arrests and houses searches, military courts without right of counsel or appeal, the burning of books, suppression of criticism by censorship, with the

police in jubilant control. Law and order are the values of the day and weighty edicts define penalties for urinating in public or hanging out the wash where it can offend the eyes of the genteel rulers. But to see the true nature of the new rulers, the manner of their coming to power must be examined. A careful

comparative timetable of the events of October 6 can be compiled from a wide range of newspapers which came out within hours of the events and which escaped the rapid police seizure. Despite the confusion and partisan coloration of the press accounts, the irrelevant detail and occasional contradictions, a reasonably accurate outline of events can be constructed on the basis of the broad underlying agreement which all the accounts reflect. After the timetable has been presented, I will conclude with some personal comments.

The Events Leading to the Coup

Many persons have long intended to demolish the strength of the students and people of Thailand. After the October 1973 incident which re-established a democratic government, it was said that if Thailand”could be rid of 10,000 to 20,000 students and other people, the country would be orderly and peaceful. During the April 1976 elections, several political parties proclaimed that “Any type of socialism is Communism,” and Kittiwutto, a monk who was also a co-leader of the Nawapol group, told the press that it was not sinful to kill Communists. There were other public statements from September to October of last year that the slaughter of the 30,000 participants at the anti-Thanom rally would be a “cost-free investment.”

Certain factions of the police and military lost their political power during the October 1973 changeover, and there were others who feared that, under democracy, they might lose their economic power. They used radio, television,

handouts, rumors, anonymous charges, and unsigned letters to attack and intimidate their opponents. The basic method of these vested interest groups was to create a fear of communism in Thailand. Anyone with whom they disagreed was branded a communist. Even Prime Minister Seni Pram oj, Kukrit and certain other ministers were not exempted from these accusations. On August 17, 1976, during a period of relative calm in the country, Prapas Charusathiara suddenly returned from exile in Taiwan. After slipping through airport customs with the help of military figures, he declared his reason for returning to be ill health and the need to obtain medical treatment for his ailing heart. Massive protests by student and other groups soon persuaded him to avail himself of the excellent facilities available elsewhere. With greater subtlety than his henchman Prapas, Thanom Kittikichorn next ap” peared, already wearing the yellow robe of a Buddhist novice.

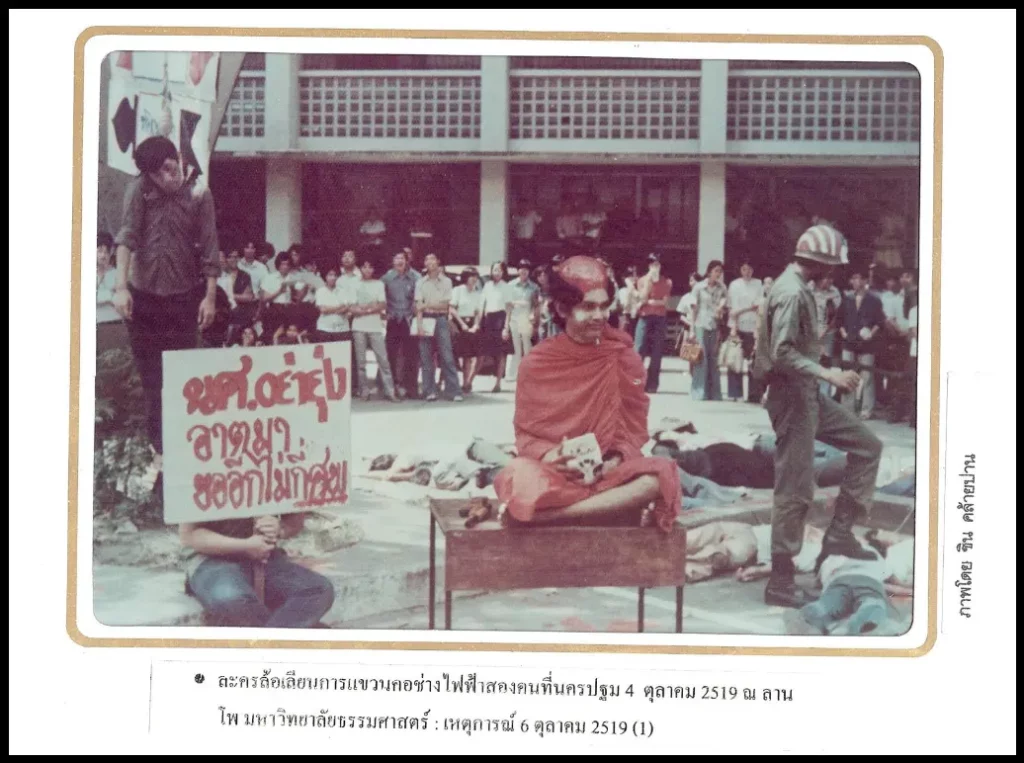

Within hours he was installed as an ordained monk in the Bangkok temple where the king himself had stayed as a monk. Thanom’s declared intention was simply to fulfill the filial duty of making merit for his ailing father. In the days that followed, a circus was enacted with the former dictator making early morning begging rounds accompanied by a massive police and military escort. Public reaction was at first restrained for fear of appearing to oppose religious values, but the emptiness of the stratagem was evident and soon students were holding mock processions of the monk and his gun-toting entourage. Posters demanding his expulsion were distributed and mass meetings organized. On September 24th, in an early omen of what was to come, two labor activists were found garroted on the outskirts of Bangkok. It appeared that they had been taken and beaten to death while posting demands for Thanom’s expulsion, and their bodies hanged nearby. It was later openly admitted that the police were involved, an admission that increased the momentum of the protests.

The members of the National Student Center of Thailand (NSCT) were joined by the “Heroes of October 14, 1973” (the wounded from the October 1973 clash in which some were permanently disabled), and by relatives of those who had died in an anti-Thanom demonstration. In early October (1976) the heroes’ relatives protested by going on a hunger strike in front of the Prime Minister’s office building.

They were harassed by the police, and, with the cooperation of the Buddhist and Cultural Association of Thammasat University, moved onto the Thammasat campus to continue protesting on Sunday, October 3.

At noon on Monday, October 4, things went as planned. There was a public gathering of students from Thammasat, and from other universities, plus a variety of other people. The demonstrators discussed the issue of Field Marshal hanom’s return and the murder of the two workers. At the demonstration, the brutal murders were reenacted realistically, and newspapers widely publicized a photograph of the mock hanging. Immediately, right-wing groups began to point out that the actor playing the part of the hanged activist closely resembled the crown prince who had just previously been summoned by the King to return to Thailand from military training in Australia. While a certain resemblance between the actor and the prince was clear from the newspaper photographs, several of my staff members who had gone to watch the demonstration had returned simply to tell me that the players had acted very well. None of them had thought that the actor’s face or the costume or the make-up made him resemble the Crown Prince. Furthermore, there is no reason why this aspect should have been exploited by the students who had always rigorously avoided any criticism of the monarchy or the royal family. Students accused right-wing newspapers of touching up the photographs to inflame the situation, and strongly reasserted what their only aim was the expulsion of Thanom, who was still following his pious rounds nearby. But the right-wing had already found the spur it needed to bring about the mob violence that followed.

The Protest of October 4, 1976

The NSCT had been planning a public gathering at the parade grounds in front of Thammasat University since Friday, October 1.

According to the students, the demonstration in part was to be used to evaluate their strength in demanding Thanom’s expulsion and the arrest and punishment of the lynching murderers. Finally, since there was a weekend market on the parade grounds on October 2 and 3, the demonstration was set for October 4.

I had heard from the students that they wished to organize this demonstration at the beginning of October because they had found out that the imminent retirement of several high-ranking officers and the annual shuffling of significant positions in the military might cause such dissatisfaction among several groups in the military as to lead to a coup.

In short the students thought that a demonstration of their strength might preclude a possible coup. At the same time they hoped to urge the government to take action on the two issues of Thanom and the hangings.

The Labor Council of Thailand joined the students by scheduling a one-hour general strike for Friday, October 8. Several newspapers wrote to Premier Seni Pramoj and asked his opinion about the public gathering organized by the NSCT at the parade grounds and about the plans to move onto the Thammasat campus.

Seni replied that these plans would be fine. Therefore the demonstration took place and, when it began raining, the demonstrators moved onto the campus at approximately 8:00 p.m. The participants remained inside the grounds of the university until Wednesday morning, October 6.

A Timetable of Events: October 6, 1976*

[*The sections of the timetable printed in italics and came anonymously to several members of the editorial board of the Bulletin via intermediaries in Singapore and in Paris. (The rest of the chronology is by Puey.) An introductory paragraph

accompanied the material:

It was a hell of blood and bullets. We could do nothing to stop them. After all it was deliberate. They wanted to kill all of us who were there. That was a comment about the bloody clash on the morning of October 6, 1976, between students and police forces at Bangkok’s Thammasat campus in which over 100 people died or were seriously injured. Several eyewitnesses and reporters were there filing their stories for Thailand Information Center’s news and features services. Here are their accounts about the events during the night of October 5 and on October 6.*]

Hours.

00:00 (Midnight) About two thousand students and others (workers and rickshaw drivers are mentioned) were gathered in Thammasat University holding a discussion, with plays and music. Some hundreds of people gather outside the gate with newspaper photographs of the alleged “prince-hanging” incident.

Wall posters are torn down and burned, and a show made of entering the university. Some police are present to assess and control the situation. Army controlled radio urges police and people to break in. To encourage civilians it said that 300 of their number were actually out-of-uniform police.

01.00 a.m. October 6, 1976 . The police director general abruptly called a meeting with other senior police officers at Bangkok’s police department. The meeting lasted over an hour. Later, all of them went to the Thammasat campus where about 4,000 students and other people were holding an anti-Thanom rally. The National Student Center of Thailand (NSCT) had organized the rally. The right wing Armour Radio called for stern police action against the NSCT. It went so far as to mourn police uibo had remained indifferent over the radio’s directives.

Village scouts and other “patriotic elements” were told to gather together for a [pro-government] counter-rally in front of the Parliament house 9 0 ‘clock the following morning.

02.35 am Police stationed in areas where the electricity, telephone and water plants were located were told to be on alert. Several members of the right-wing militant group, the Red Gaur [named for the wild ox] asked the NSCT’s security guards to enter the’ campus, saying that they have changed their minds toward the NSCT.

They burned their Red Gaur membership cards. However, once inside, they are said to have subverted the rally.

03.00 am Special police forces or anti-not police completely encircle the university, including three police boats on the [Chao Phraya) river that forms the rear boundary of the university. A police headquarters is set up at the nearby National Museum, indicating the seriousness of the operation envisaged.

When the Police Chief arrived with other key officers at a nearby station, he declared his intention to clear the university at dawn and to arrest the culprits of the alleged lese-majeste incident. Questioned on the responsibility for such a command, he replied that it was his own. Crowd at gate set fire to a rubbish cart and try to stir up the situation by throwing burning objects into Thammasat. No reaction from the students.

04.00 am Police report seeing armed students near river bank and warn boats not to aid escape. Incidents at gate increase, led by right-wing paramilitary Red Gaurs.

Sentry box burned and burning objects thrown. Numbers increase. Some gunfire in the area reported.

04.00 am The first shots came from outside the university. A special unit of parachute police were called in from outlying provinces in the south. They were airlifted by helicopters, but did not arrive at the campus until about 8 a.m.

05.00 am Serious shooting breaks out as Red Gaurs and others make attempts to break in. Missiles including explosives and handgrenades thrown in. Explosion occurs where students are gathering and many injured, some seriously. At this stage Red Gaurs lead the armed offensive with police acquiescence. Students hold off attack by firing and one man shot in chest. (He later died as he was taken to hospital.)

Students take cover in the buildings of the university.

05.40 am Police began to fire from the M79 rocket launcher [near the museum]. There was a big explosion in front [part] of the campus. As a result, 16 people were simultaneously injured, eight seriously wounded, and one killed. The Red Gaurs, police and soldiers tried to enter the campus. The crowd of 4,000 which have been in the campus since October 4 began to disperse, rushing to several buildings which surround the rally ground. The crowd was even more frightened when firing followed, apparently from M16 and AK33 assault rifles. The NSCT’s security guards resisted by firing back.

05.50 am Some members of the Red Gaurs and the village scouts tried to break through the campus gate by using a bus that they had hijacked several hours earlier. Police, Red Gaurs and soldiers followed suit by climbing the iron wall which guards the university. Some of them managed to get in. The Armour Radio, meanwhile, called for a total surrender on the part of the NSCT. It also claimed that police had been injured by the students’ firing. Apparently the crowd in the campus were not aware that they had been under attack from both the

police and the Red Gaurs. Their impression at the time was that the NSCT’s security guards were fighting with the Red Gaurs who had tried to come in as before. Seeing that firing had become intensified, they tried to get out. However, all the exits were blocked.

06.00 am A small number of wounded are brought out by ambulance, two by boat. Further evacuation by boat stopped by police. Sounds of automatic rifles heard. Police sharpshooters begin to fire. Police in boats claim that students had

opened fire with handguns, later they claimed heavy weapons such as M-16s and AK-47s were used. Navy police reinforce river. Simultaneous firing from river and other side of the university by both police and Red Gaurs. Student leaders,

realising the scale of the attack, consult persons at the rally; they declare that they must fight back having nothing further to lose. Speaker announces many may die but appeals to students who survive to transmit their anger.

06.00 am Realizing that the situation had become worse, the NSCT’s leaders tried to contact the Prime Minister’s secretary to ask for a negotiation with the Prime Minister himself The NSCT’s leaders also reported on what had been going on.

The secretary, however, reported that his sources had told him that it was the NSCT security guards who opened fire and that it was the police who were wounded, not the students. He agreed to arrange for a meeting with the Prime Minister under the condition that the student, who, a few days earlier had played a part ofthe lynched activist and happens to have a face quite similar to the crown prince, were to come along. The NSCT said it needed time to think about the proposal.

Meanwhile the death toll had increased to four persons. In an attempt to escape from the shooting, students retreated to the river bank behind the campus. Some of them escaped into the river only to find that the navy patrollers fired on them. Those students who tried to take the wounded out [of the campus compound] to the hospitals were not allowed to leave. The police had blocked all the exits.

06.15 am The fighting kept on. The NSCT appealed for a cease fire and said that they were willing to surrender before more died. There was no response from the police.

06.20 am Border-patrol police and police from every other station in Bangkok were mobilized to the campus.

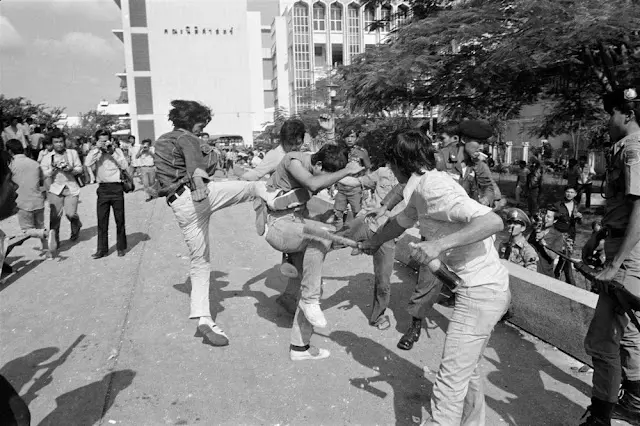

06.30 am Another three students died as the M-79 rocket launcher was fired from near the museum. The NSCT again appealed for a total ceasefire and added that the wounded should be sent to hospitals.

Not only was there no response; the Red Gaur and police again attacked students who tried to get out of the campus. The NSCT leaders again called the Prime Minister’s secretary to say that they were willing to disband the rally and ask for police protection. The secretary reportedly agreed.

07.00 am Firing continues, police numbers increase. Some police injured. Three of the injuries (including one case in which a policeman’s fingers were blown off) were caused by a Red Gaur car bomb that misdirected and exploded. Police claim that student weaponry is more efficient than their own.

They call for reinforcements. Right-wing groups use two buses to crash through gates but back out as police fire from behind them continues. Police order all escape routes blocked and forbid boats to respond to appeals.

Sutham Saengprathurn, leader of the National Student Council of Thailand, and five student representatives, including the student who had acted in the controversial hanging incident, come out in ambulance and go in police car to the Prime Minister’s house. They report many students are wounded. Their request to speak with the Prime Minister is denied and they are arrested by police.

The Prime Minister later told the press that tbe NSCT leaders had offered themselves to the police. In an interview to the press later that morning, the NSCT’s secretary denied the Prime Minister’s story, saying:

We have been cheated. They first told us that we could talk things out; but when we went there for a talk, they arrested us. What does this mean? We again confirm that what we have done is a right thing. We ask the people to judge the whole thing.

Police in front of the campus were quoted as having said that tbey would kill as many students as possible: “When they see students killed, they appear to be happy.”

07.10 am The NSCT’s political secretary, together with security guards, asked the police at one of the exits for permission to take the wounded out. No success. The shooting went on without interruption, and deaths were on the rise.

The student rally’s announcer who was announcing “we are willing to surrender” was killed immediately by an M-16 rifle shot.

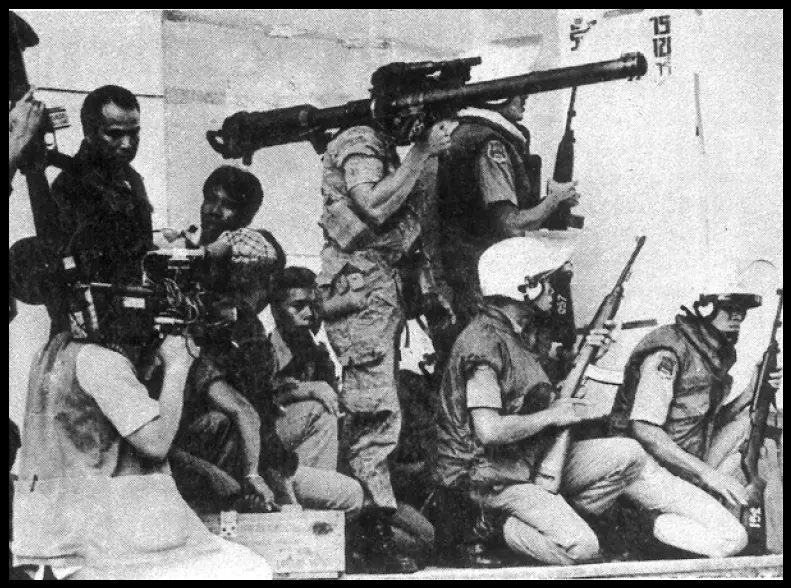

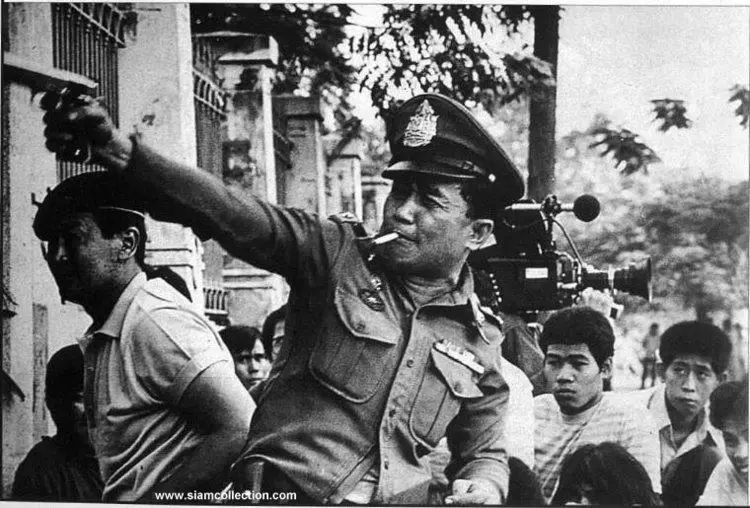

07.30 am “Free fire” orders given to police “to defend themselves.” Police reinforcements arrive including over a hundred Border Patrol Police with heavy weaponry, hand grenade launchers, etc. Police paratroopers from Hua Hin also arrive. Bangkok police come, including Bangkok Police Chief who, declaring he is ‘ready to die,” joins in the shooting.

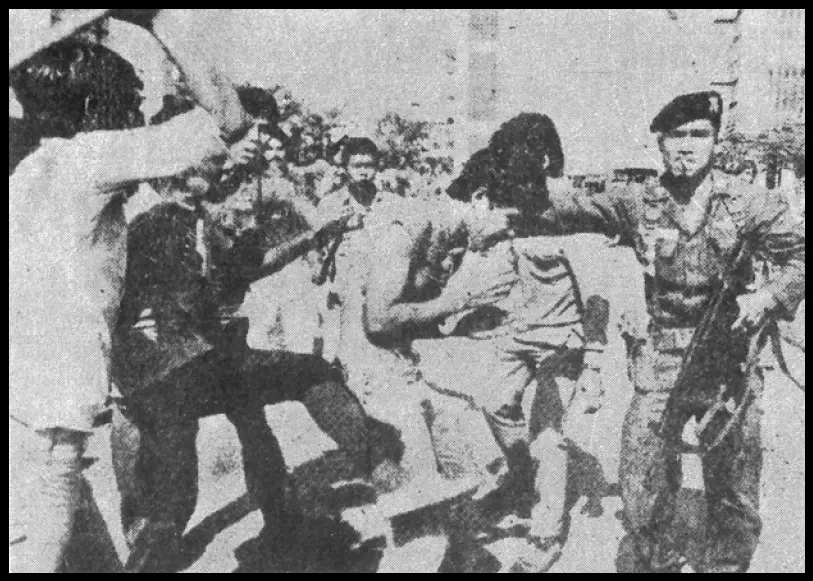

Police began invasion of Thammasat. Many students wounded and killed. Student appeal to evacuate girls ignored. Some police wounded by student fire.

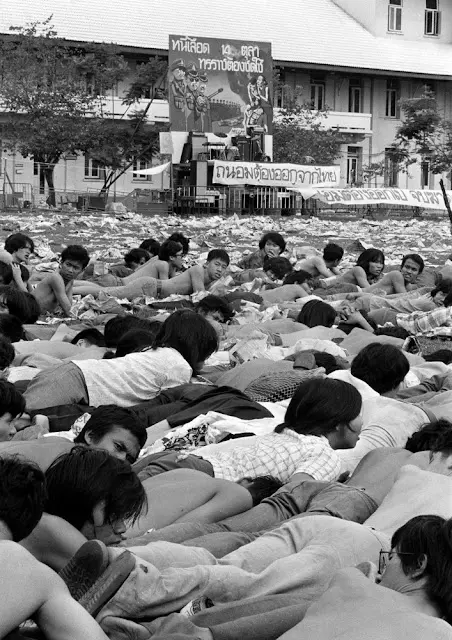

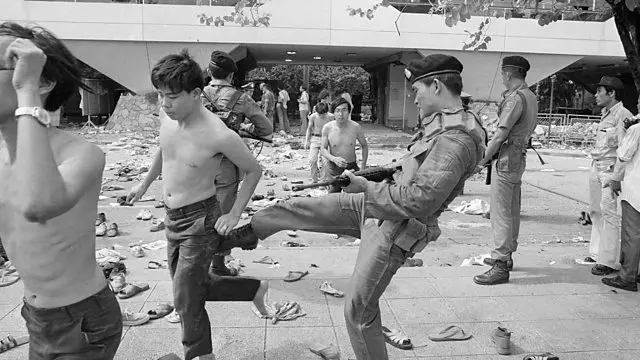

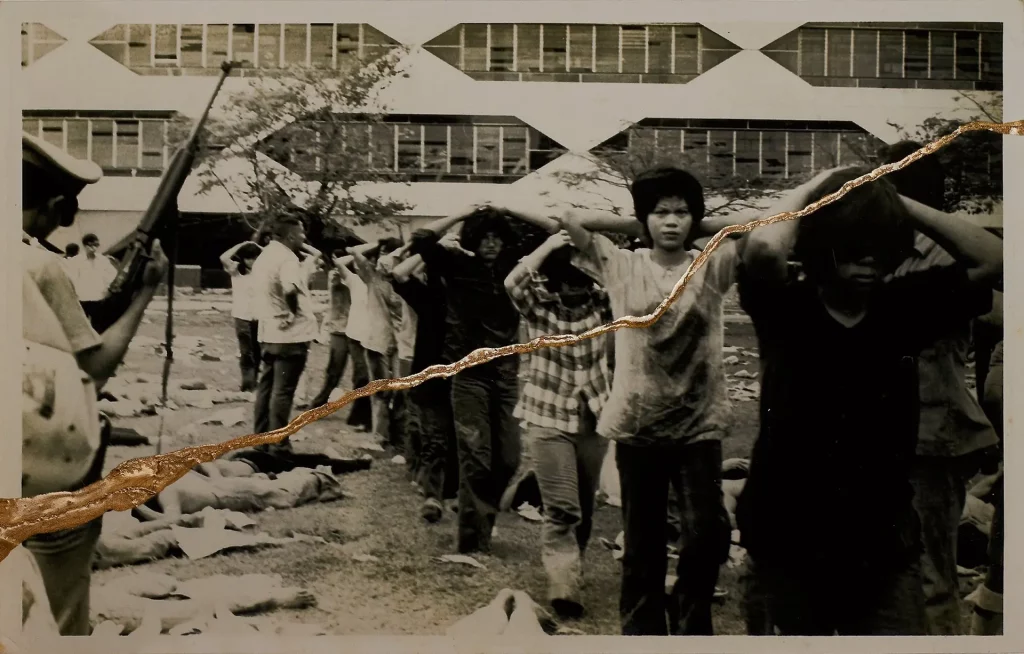

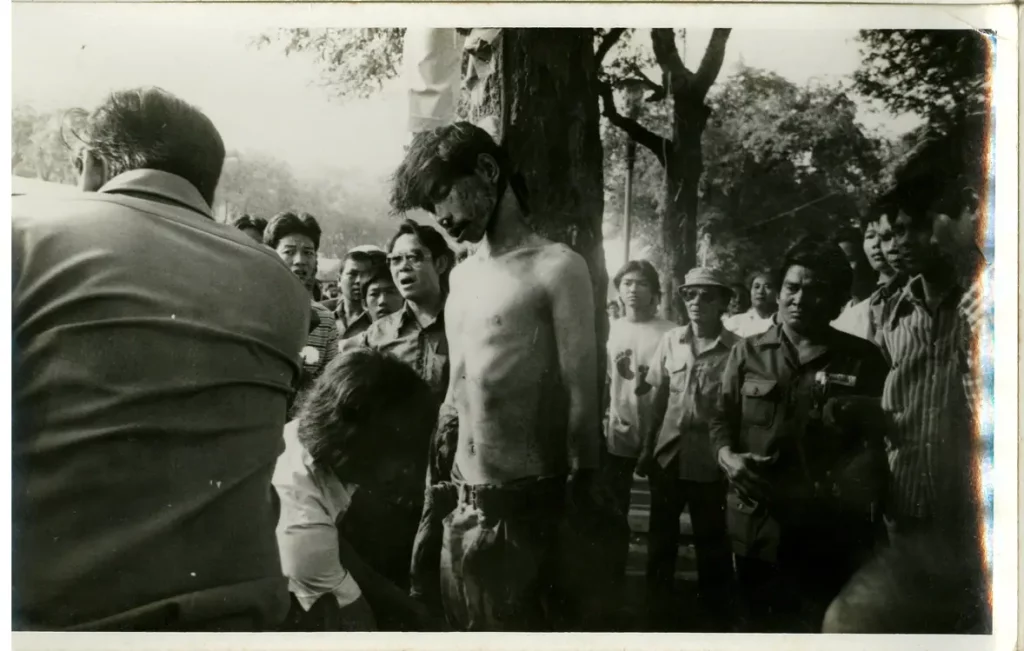

More students tried to escape from the figbting by jumping into the river. Police navy patrollers shot at them indiscriminately. Several hundred others were arrested. With their shirts taken off; they were forced to lie down with their hands on the backs of their heads. Many were severely beaten. Many drowned [in the river]. The right-wing Armour Radio called on police to search carefully on tbe campus and in the nearby temples. Police started shooting from every side of the campus.

07.45 am Police on tbe southern side of the campus uiarned people to stay out. An explosion erupted and one policeman died.

08.00 am Police estimate seeing 20 students armed with handguns and rifles. Appeal to evacuate 50 wounded across river ignored.

08.15 am Massive attack by Border Patrol Police and Red Gaur groups. Explosions every minute, probably from M-79 grenade launchers carried by Border Patrol Police. Rounds from heavy weapons carryover to food shops outside. Villagers on roof tops encourage police, saying students have no heavy guns.

08.20 am Parachute police who had been airlifted from the south arrived. It was reported that a United Press International pbotograpber had been shot and tbat the students who had escaped into the river bad been fired on.

08.35 am Fighting was particularly intense.

08.37 am Students who had been arrested on the opposite bank of the river continued to lie on the footpath with their shirts off and their hands on their heads. They were to remain in that position for three hours. Those who had sought refuge in the nearby shops were told to give up, or else the police would fire indiscriminately into the shops which refused to open their gates.

08.50 am The right wing groups began to hold a rally in front of the Parliament House. They were joined by Village Scouts who had finished their mission in front of the Thammasat University campus.

08.55 am Students who tried to escape through the front gate were greeted by right-wing militants, the Red Gaur, and scores of police and soldiers who began to beat, club and fire at them. One student, his head severely beaten at the front gate, was shot in the presence of policemen. The student was later hung. A woman, apparently shocked by the outright brutality, asked: “Why must we Thais kill each other? Have we forgotten how many lives were sacrificed driving out the tyrant trio three years ago?” No sooner had she finished speaking when a man rushed out of the crowd, pointing a finger at her. He threatened her and said: “Do you want to die? Are you Vietnamese, you social scum?” Students and others in the campus were herded by the police onto the football grounds and forced to lie down with their shirts off Both boys and girls.

09.00 am Period of heavy fighting as police attack individual buildings and student bases. Two police killed. Many students wounded and killed.

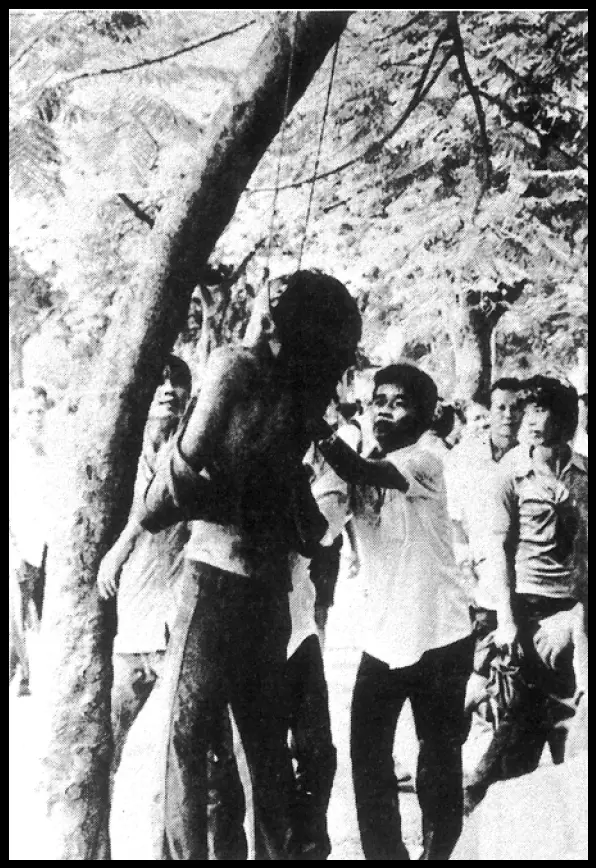

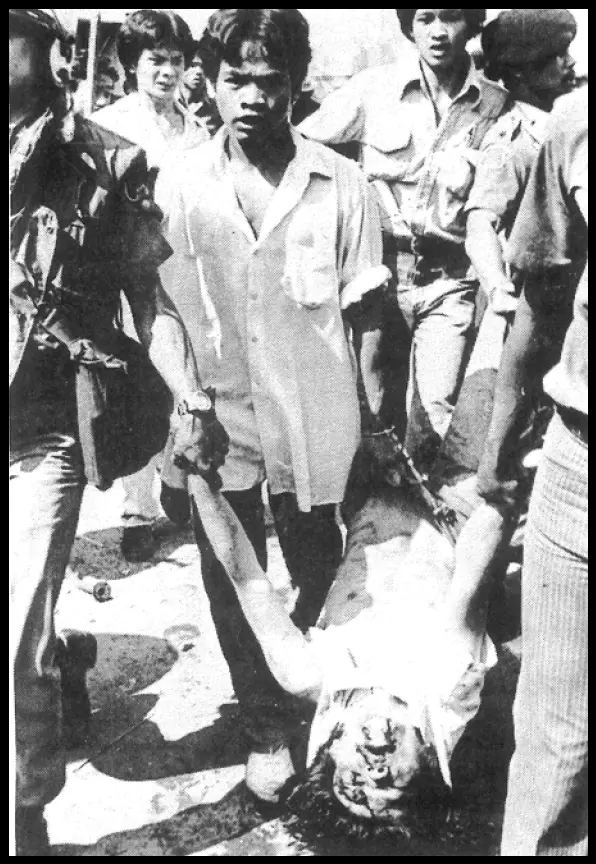

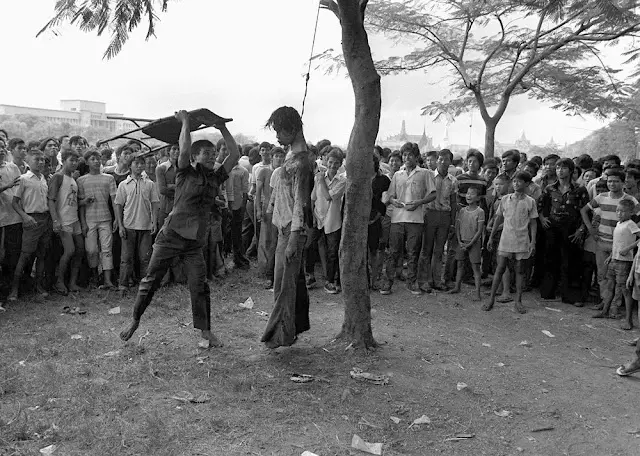

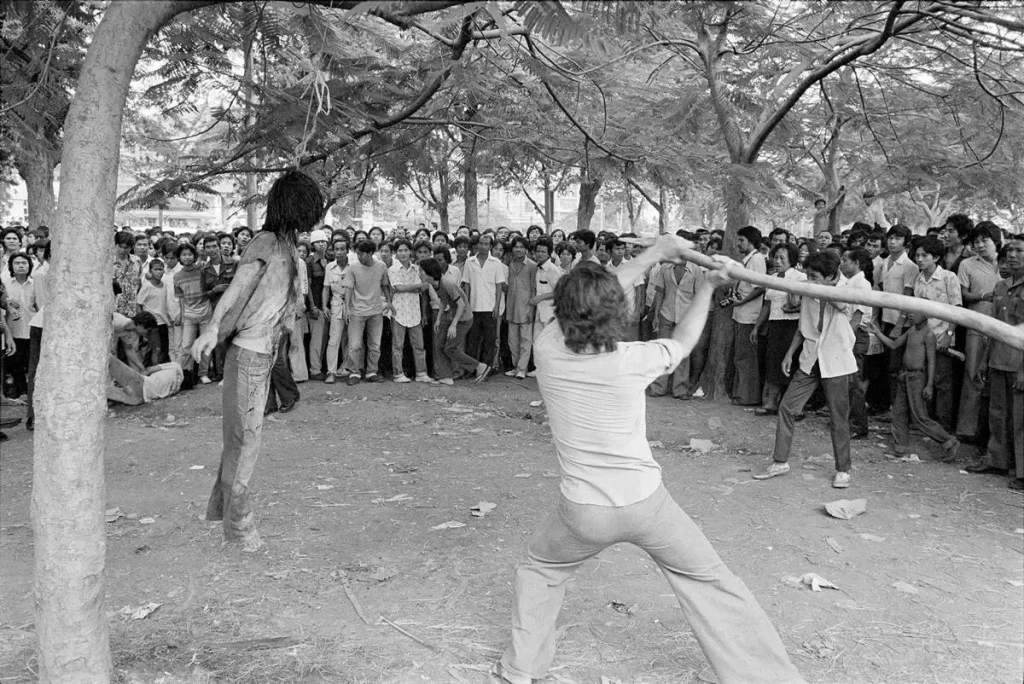

While police use heavy weaponry, Red Gaurs, Village Scouts and right-wing groups, having seized ten to fifteen wounded or escaping students including two girls, beat, mutilate, hang and burn them, occasionally with police watching.

One girl stripped and shot repeatedly. Large numbers of students try to escape but are arrested.

09.06 am The Red Gaurs began to pour kerosene on and to burn four people, one ofwhom was still alive.

09.20 am Four students, their hands on their heads symbolizing surrender, came out through the front gate and were brutally beaten and shot by the Red Gaurs. One was hung. A girl, who had been shot to death, was sexually abused by plainclothes policemen; they used a stick on her vagina. At a nearby site, a man was severely beaten and burned. Another person was hung while he was still alive.

09.30 am Meanwhile a Cabinet meeting was going on. Right-wing factions demanded the the three alleged communist ministers be dismissed. Prime Minister Seni Pramoj, saying that the Cabinet had just been apppointed by the King 24 hours earlier, refused to do so. At a press conference, the Prime Minister tried to dissociate himself from the violence at Thammasat while admitting that he had ordered the police to clear the campus. He said, “It’s up to the police to decide whether to use violent methods or not. “

10.00 am Students were taken to prisons in big buses. On their way they were occasionally beaten or robbed of their valuables as right-wing hooligans entered the buses.

Several students who tried to escape from the buses were shot by the police.

10.00 am More students are brought to football field as they are arrested. Right-wing groups wander about kicking bodies, tearing off Buddhist emblems saying, “these communists are not really Buddhists.” Atrocities continue outside Thammasat. Units of special action police stand and watch as two are hanged. Bodies dragged out, mutilated and burned. Large crowds watch. Several wounded or arrested students dragged from police and beaten or lynched. Police try to stop this action by firing in air; they manage to rescue one girl.

10.30 am Police began searches in the university; rightwing elements followed suit. Fighting began to cease. Meanwhile, the crowd in front ofthe Parliament increased.

11.00 am Renewed fighting in Thammasat. Police ordered to clear completely. Efforts by youths to seize wounded on way to hospital. Events tail off.

13.00 am As rain poured down, the whole area in front of the Commerce Department building, where the heaviest fighting happened a few hours earlier, turned red with blood.

18.00 am The crown prince addressed the Village Scouts who had moved on to the government house. He asked the crowd to disperse. An announcement was made that the country was being taken over by a group of military officers calling themselves “the national administrative reform council.” Martial law was introduced and Bangkok’s three years of experiment with a parliamentary system came to an end.

Note: According to figures released by the new regime, 41 persons died and several hundred people were injured. About 3,037 persons were taken prisoner of whom about over 600 were female.

However, sources at the Chinese Benevolent Foundation, which transported and cremated the dead, it was revealed that they had handled “over a hundred corpses” that day. Certain key aspects of the outline of events may be noted:

a) The meeting in Thammasat was no different from many others which had been organized at the return or Prapas or since the coming of Thanom. Students were well aware that they could expect little protection from police if attacked by armed right-wing groups. They would certainly have organized some defence. A Red Gaur attack during an anti-Prapas rally in Thammasat some weeks before had resulted in two deaths.

b) During the assault on Thammasat, the Armoured Brigade Radio had been exaggerating and playing up the rumor that there were heavy weapons inside Thammasat. It claimed that there were grenades, heavy machine guns, and other heavy arms. This was a totally false accusation which had been used ever since 1974. But whenever time comes to prove the truth, such as the Red Gaurs’ assault in August 1975 and the search after the rally against Gen. Prapas, the police have been unable to produce evidence to show that any weapons were hidden inside Thammasat.

This time, what the police could produce to the public were only two rifles. There were no heavy arms such as machine guns. The accusation was unquestionably made up out of thin air.

Ever since the end of 1974, politicians and some student leaders had found it necessary to carry arms in order to protect themselves. At that time, the Red Gaur units, police, and soldiers had already started to impose physical harm on worker leaders, peasant leaders, student leaders, and occasionally politicians. And the police have never apprehended the murderers. (But in similar circumstances when a policeman killed another policeman, or someone tried to kill a politician who belonged to the Government’s party, the police were able to arrest the murderers without hesitation.)

From the night of Monday, October 4, to the morning of Wednesday, October 6, the students and civilians had opportunities to bring those weapons inside the university. Both the protesters and the Red Gaurs had an equal opportunity.

c) There were three most critical stages in the course of events: 1) the police refusal to listen to student appeals for a ceasefire between 6:30 and 7:00 a.rn., 2) the “free fire” order at about 7:30 a.m.; and c) the invasion by Border Patrol Police

with heavy weaponry after 8 :00 a.m, The overall sequence of events may be summarized as follows. Police allowed right-wing groups to take the initiative

in provoking a critical situation around a lawful student gathering which they sealed off so that no escape was possible.

As defensive student action developed, police began an attack which culminated in a massive onslaught with heavy weaponry by combat units, causing heavy student casualties. Police allowed-or made ineffective efforts to prevent-brutal and savage mob attacks on helpless students. 39 students died, while hundreds were wounded. Police casualties were two dead and about thirty wounded. Clear photographic evidence of details of the events accompanied published news stories. Some background events also derived from first newspaper reports help one to understand what occurred.

Right-wing groups were mobilizing continually to initiate and to support the police attack. As the hours went by, Village Scouts and others gathered from the city and countryside to join in the massive blow to student activity.

By 9:30 a.m. a crowd of 30,000 had already gathered at the equestrian statue of King Chulalongkorn, coming by bus loads from as far off as Ayutthaya.

The radio of the armed forces (Free Radio Group and Patriotic Peoples Group) played a major part in stirring up hatred against the students. During the night of the 5th and 6th it broadcast all night long a series of violent and emotional

speeches, at times calling out to “Kill them … kill them.”

The order for the police invasion of Thammasat was given by Police General Sisuv Mahinthorathet. The invasion was said to be the consequence of an order given by the Prime Minister to arrest those involved in the alleged lese majeste incident of two days before. Both the Prime Minister and the police later declared that the “clearing” action was made necessary by attacks on the police as they attempted to carry out the arrest. The Prime Minister replied to reporters’ questions that the decision to use heavy weaponry was the affair of the police department. However, police later produced a copy of the Prime Minister’s arrest order.

It bore the time 7 :30 a.m. on October 6th. Moreover, newspaper reports indicate that police sharpshooters had begun to attack much earlier, while the students directly involved in the supposed lese majeste incident-those who had come from Thammasat to parley with the Prime Minister-had already been arrested soon after 7 :00 a.m.!

Two Comments

Student and labor forces have perceived the successive returns of Prapas and Thanom to be deliberate probes by coup manipulators. As no issue touching the short-term interests of the majority of the population appeared to be at stake,

students were drawn into a stance of virtuaJly isolated protest.

Aware of the strategy of the coup-makers, they stiJl hoped to prevent it by the threat of massive demonstrations and national strikes. Before October 6th it was indeed difficult to envisage any possible way in which a junta could survive the

reaction that seemed inevitable. The events of the few hours on the morning of October 6th created a situation in which further protests were impossible.

Students were stunned by the horror of what they had heard and seen. Many could not sleep the following night, and as they scattered to avoid further retaliation they lost contact with each other. Considering the manner of the coup, it appears logical to conclude that the events of October 6th were a carefully planned drama leading to a long-prepared conclusion.

The circumstances recall the remarks of CIA director William Colby when he said that the bloody executions which accompanied the military in Chile in September 1973 had done “some good” because they reduced the chances that civil war would break out in Chile.

American advisers have long directed Thai anti-insurgency operations and their methods stand out clearly by contrast with the more direct tactics of the Thai military who have shot up whole viJlages, or burned their victims in tar barrels.

During the past year a “Phoenix’l-like programme bearing every resemblance to its original Vietnamese version has operated to eliminate popular peasant, student, and political leaders. One American anti-insurgency officer admitted to me that in the period foJlowing the withdrawal of American armed forces their anti-insurgency operations would continue, mainly at the political level.

Thousands of “advisers” would remain at every level of government, military and police activity. CIA coup-making experience needs no further comment.

On an ideological plane, action against the students had been prepared by labeling them as “a communist threat.” On October 6th the government spread ridiculous charges about Vietnamese infiltration; they claimed that there were non-Thai speakers among the students at Thammasat, or that eight armed Vietnamese were seen entering a temple.

One dead body was identified as a Vietnamese sapper. As evidence, the police produced an amulet bearing the words “Oriental Horoscope” and another with “some letters that” might be Vietnamese.

Proof didn’t really matter because, for months before, right-wing groups had been imbued with the idea that the students were communists.

As counter-insurgency “experts” had learned in Vietnam, it is not enough to muster forces against the adversary. Also any attempts to instill a fear of losing either liberty or economic advantage had little effect on people who had neither.

Therefore it was considered far more necessary to create a powerful emotional appeal to the population at large.

In Thailand strong popular attachments to “King, Religion and Country” were used as a wedge to alienate people from the students. These ideas were instilled in various organizations such as the Nawapol, Red Gaurs and especially the Village Scouts, which” were under the direct patronage of the royal family. These groups are the “people” whose rejection of the students is being repeated ad nauseam by radio, television and newspaper.

Right Wing Groups and the Military

The Red Gaurs

The Red Gaurs is an organization set up by the Internal Security Operations Command (IS0C) of the Thai military (itself the product of American CIA counter-insurgency planning in Thailand). Some of the merribers of the Red Gaurs were vocational students who have graduated, some who haven’t graduated, and some who did not attend school at all.

ISOC set up this organization in order to negate the student movement after the October 1973 incident. Ever since the time we were drafting the Constitution in early 1974, the foreign press had been reporting and naming Col. Sudsai Hasadin as the main organizer and supporter of the Red Gaurs.

There has never been a denial by him of this allegation. ISOC was the organizer, trainer, arms supplier, and funder of this group. As a result, ever since the middle of 1974, the Red Gaurs’ units have been publicly armed with various types of guns and grenades.

No policeman or soldier would arrest or give these armed civilians warning. No matter how peacefully the other students might stage a demonstration, the Red Gaurs would always threaten them with these weapons.

In the protests against some articles in the newly written constitution in 1974, against the American military bases in 1974-1975, in the assault on Thammasat in August 1975, and during the protests against the returns of Field Marshals Prapas and Thanom, the armed Red Gaurs were responsible for numerous casualties. Newspaper photographers who tried to take pictures of the Red Gaurs carrying weapons were frequently attacked and injured.

In the election of April 1976, the Red Gaurs harassed candidates and assaulted some so-called “leftist” political parties.

Nawapol

Besides instigating Red Gaur violence, ISOC played an important role in forming other groups and units useful to the military during this period of civilian rule, auch as Nawapol.

Nawapol is similar to the Red Gaurs in some ways, but it is more like a psychological warfare unit; its mission is to cooperate with the Red Gaurs. The organization has attempted to rally together the merchants, businessmen, and monks who do not wish .to see social change and development along

democratic lines, and who were against the student and labor movements.

By publishing articles and convening conferences and rallies, Nawapol’s central method has been to convince the privileged that even a change toward democracy might deprive them of possessions. Mr. Wattana Kiewvimol, the Nawapol director, was asked by General Saiyud (the head of ISOC) to come back from America to teach psychological warfare techniques at ISOC.

At times some people have been misled to believe that Nawapol aimed to build a new society through the use of cooperatives, but in reality its purpose has been to preserve old conditions for the benefit of the businessmen and landlords.

Village Scouts

Another important organization, the Village Scouts, were allegedly set up to be non-political. Actually, they have been political tools of the business and landlord groups. Their true nature was observable in the April 1976 elections, at which time they campaigned heavily-and with some success-for right-wing and military candidates. The overall organization of the Village Scouts claims primary loyalty to the Nation, Religion, and King. The Ministry of the Interior played an important role in organizing the Village Scouts, and wealthy businessmen and merchants supported them financially. The role of the Village Scouts as the “outraged mob”

on October 6 was clear evidence of the true purpose of this organization.

Aside from the Red Gaurs, Nawapol, and the Village Scouts, ISOC and the Ministry of the Interior also used other groups with different names. Some are affiliated with, or are simply front groups for, Nawapol and the Red Gaurs , such as the Thai Bats, Housewives’ Club, Thailand’s Protectors, etc. The operational tools of these groups were anonymous cards, leaflets, flyers, and phone threats.

In addition to the open operations of these groups, political assassinations had begun in 1974 as well. Peasants’ and workers’ representatives were ambushed one by one throughout the country. Student leaders were killed in Bangkok and other cities, and politicians such as Dr. Boonsanong Poonyodyana, the Secretary General of the Socialist Party, became the victims of these assassins as well.

Each time, the police failed to find the murderers, perhaps because they took part in each murder.

Violence in Thailand

It might appear that the gentle and non-violent tenets of Buddhism would hinder the build-up of hatred exemplified in these assassinations and in the violence by the “mob” on October 6th.

But a spokesman for violence was found in a monk called “Kittiwuttho Bhikku” (Kittinak ]araensathapawn).

In an interview published ‘in the liberal magazine Jatturat, this favorite consultant of right-wing groups rationalized the killing of left-wing activists and communists by saying:

I think that even Thais who believe in Buddhism should do it [kill leftists]. Whoever destroys the nation, religion and king is not a complete man , so to kill them is not like killing a man . We should be convinced that not a man but a devil is killed. This is the duty ofevery Thai person.

Question: But isn’t killing a transgression?

Yes, but only a small one when compared to the good of defending nation, religion and king. To act in this way is to gain merit in spite of the little sin. It is like killing a fish to cook for a monk. To kill the fish is a little sin, but to give to the monk is a greater good.

Question: So the ones who kill leftists escape arrest on account of the merit they gain.

Probably.

In the incident of the mock hanging, the charge that the person being “hung” resembled the prince was given as the immediate source of the fury of the mob on October 6.

Rumors of Vietnamese incursion suggested the nation was under attack. The rationalizations of Kittiwuttho Bikkhu gave license to kill.

When the junta stepped in they posed as the upholders of the King, Country and Religion. Subsequently the identity of the monarchy with the new regime has been emphasized, as well as the part played by the crown prince who returned for unexplained reasons on October 2.

One of his first acts was to visit and pay his respects at Wat Bovornnives where Thanom was living. After the coup, newspapers carried daily photographs of the prince in the company of army and police officers. Both he and the king himself are also shown receiving the homage of Village Scouts who had gained so much “merit” in the events of October 6.

Finally, the two royal princesses have done their part by being photographed with wounded policemen in Bangkok hospitals.

How neatly the parts fit together! But the key to the plot lies in the events of October 6 that have been outlined.

For it is completely inexplicable that a police commander would accept responsibility for the killings in Thammasat if he had not received the assurance that the events would lead to a military coup. Right-wing groups and police were the agents, while the military kept discreetly away. During the mob violence of the morning, police declared they were still in control and rejected suggestions that the military be called in.

Yet as soon as the coup was announced, the alliance of police and military came into the open as combined squads set out together on search and book-burning sorties.

“King, Religion and Country.” These are the values around which the military junta, closely knit to the monarchy, police, and the Village Scouts, professes to take its stand. The dead of October 6th are being explained away and forgotten;

they are said to have been rejected by the “people.” Students are fleeing the country into Laos or to the jungle to join the armed struggle. Others remain, with bitterness hidden in their hearts, awaiting the day when the people will speak again and stir to move history forward.

Related Links: